It is almost impossible to consider Goldie’s work in Sligo without reference to the Bishop of Elphin, Laurence Gillooly. Goldie had already been engaged by Gillooly to complete work on St. Vincent’s church in Cork and on the attached Vincentian presbytery. Gillooly was a Vincentian and was educated in the Irish College in Paris.(Bowen, 2006, p.225) He was appointed Bishop of Elphin, which incorporated parts of the counties of Roscommon, Sligo, Westmeath and Galway, in 1858. According to Cullen, Gillooly was involved in the construction of thirty churches, along with many convents and schools. (Canning, 1987, p.340) When we consider the dates for churches built in the nearby diocese of Achonry, such as St. Nathy’s, it is possible that Bishop Gillooly became aware of Goldie’s work during his term as Coadjutor Bishop of Elphin (1855-6) while still Superior at St. Vincent’s.(Canning, 1987) Goldie also carried out improvements on a Vincentian church in Sheffield in 1856. He would also be involved in other Vincentian buildings in Ireland such as St. Peter’s, Phibsboro and Castleknock College. Aside from these circumstances of possible awareness of the architect’s work, it is difficult to definitively state how the connection between Goldie and Gillooly came to be but whatever the root of the friendship it would lead to a very fruitful partnership between the architect and the bishop.

Goldie built two convents, and three churches in Sligo, including the cathedral and the Bishop of Elphin’s residence; he also designed the Bishop’s crozier, which is still in use to this day. Not all of the churches in Sligo came under the remit of Bishop Gillooly, Ballymote is in the diocese of Achonry, just as not all churches in Roscommon were part of the diocese of Achonry, such as Strokestown and Castlerea which were part of Elphin. The other churches within the diocese designed by Goldie are discussed under their relative counties.

Church of the Immaculate Conception, Ballymote, (1859-62).

The site for the church was granted rent free by the owner of the town, and grand-father of Countess Markievicz, Sir Robert Gore-Booth. (swords, 2007, p.52)The first tender invitations for the building of Ballymote church in the diocese of Achonry were advertised in 1859. By October 1859, the same newspaper was discussing the merits of the church building describing it as thirteenth-century Gothic in style with ‘a rose window of most beautiful and novel form.’ It was also mentioned that the cost of the church would be £3,000, without including the tower and spires. In the event, it seems that only the tower was built but, even so, this creates a very well-proportioned building with a robust and powerful stature. The Evening Freeman declared in 1861 that the beauty of the church was not due to any elaborate ornamentation but came as a result of its ‘graceful and harmonious outline and proportion.’The building, although based on thirteenth-century gothic, sported none of the elaborate decoration found on the exterior of such churches but was adapted to the properties of the local materials and circumstance and displayed ‘simple geometric forms.’

In June 1861, a report from Goldie to the building committee was carried in the Sligo Champion. The report outlined the progress on the building, the finances expended and the urgent requirement of additional funding to complete the important roofing phase of the project. In June 1862, the Parish Priest of Ballymote Fr. Tighe, the individual responsible for the endeavours to build the church, wrote to the Sligo Champion outlining how the work had progressed and mentioned some of the financial supporters that helped see the task through to completion. In 1869, Tighe again wrote to the Champion to report on the addition of the tower and to thank the many benefactors who had assisted in the past and were continuing to do so.

The dedication of the church took place in September 1864 and was covered widely in the press at the time. The church was described as ‘one of the most spacious, most substantial, and at the same time one of the handsomest temples of Catholic worship to be found in the country districts of Ireland.’Close to the church were the ruins of ‘the venerable Abbey of Ballymote, founded by St. Columbkille and the same in which the famous book of Ballymote was written.’

Gothic revival in style, the church is a strong presence in the town’s landscape. The ashlar limestone used in its construction adds to its robust appearance. In the main portal there is an interesting mosaic feature and the interior presents a well lit and open space that invites the attendance to engage with the stained glass of the clearstory, rose window and lancet windows. The mosaic feature of the entrance is continued in the interior.

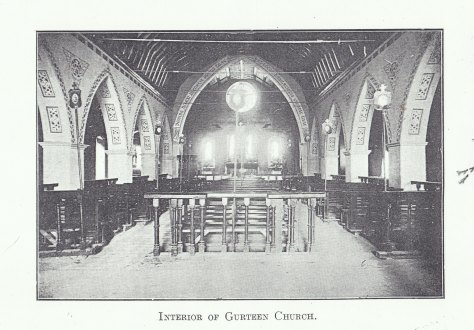

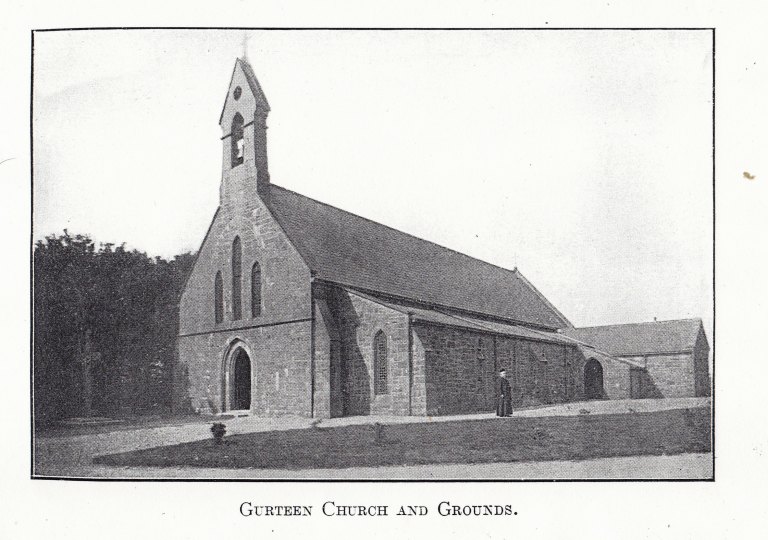

St. Patrick’s Church, Gurteen.

The church of Saint Patrick was built in Gurteen in 1866. The name of the parish was Kilfree and this is how the church was referred to in newspaper reports of its dedication in November 1866.According to the official parish website (http://gurteenparish.com/links.aspx )the church designed by Goldie replaced an earlier church in the same site built in 1829, just after Catholic Emancipation had been achieved. The earlier church was described by Lewis as ‘a large chapel.’[1] Goldie’s church was described a ‘in the pointed Gothic style’ and able to accommodate 1,200 parishioners. The foundation stone for the church was laid in May 1866 but by August the building of the church ran into difficulties due to a lack of funding to complete the roofing of the church. The permission given by the bishop of Achonry to allow the parish priest, Roger Brennan, to seek support and financial assistance outside of the parish was due to the impoverishment of the people of the area, unable to raise adequate funds themselves. Even with these difficulties, the church was completed by November of the same year.

There were alterations to the church carried out in 1919 but early photographs show that, although the altar appears to have been changed, much of the interior and exterior of the church remained largely unaltered.

An interesting incident occurred in the church in 1882 . Damage was done to the altar and pews were smashed and removed in protest, this may have been linked to former members of the Land League as one of the seats targeted was that of the local landlord.

[1] Lewis, Samuel, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland, Vol.II, 95.

Ursuline Convent of St. Joseph

In early 2019 planning permission was being sought to convert the convent to a nursing home and housing development. The building had ceased to function as a convent in 2004 when the nuns moved from the premises and some of the rooms where incorporated into the attached Ursuline College. The departure of the nuns from this wonderful example of Gothic Revival architecture saw the end of a continuous occupancy of over 150 years.

The convent had been built in 1850, around the same time that the Mercy Order moved in to a new convent in the same quarter of the town of Sligo. The press reports of the time pointed to the anti-Catholic ‘bigotry’ that had prevented the establishment of religious convents in the earlier part of the century.Goldie’s intervention came in 1862 when he designed the extensive new wings to the convent that would provide additional class-rooms and dormitories. Given Goldie’s future work on other Ursuline convents, in Ireland and in the U.K., it is unlikely that his input was limited to just the wings. A report in the Sligo Champion in July 1863 mentions the ‘new and expensive buildings which have been added to the convent’ that included a new library and chapel. The chapel within the adjoining school has many of the hall marks of a Goldie convent chapel – the NIAH suggests that the chapel was added around 1870, a year when Goldie was working on the nearby Sligo Cathedral so it is very possible that the chapel is part of his oeuvre.

The Dictionary of Irish Architects suggests that George Goldie’s work on the convent occurred in around 1862 from sources in The Builder .This is very likely as it coincides with the timescale for his other work in the town. According to The Builder Goldie’s input comprised of the addition of ‘a new porch and belfry.’ The DIA also raises the possibility that the chapel was also designed by Goldie, again, this would not be surprising given his reputation, his other work in Sligo and in the Diocese of Elphin, and that he was also working on the Ursuline Convent around this time. Jeremy Williams states that Goldie’s work on the building was ‘the best addition architecturally.’(Williams, 1994, p.337)

Although the convent is now used as a residence for asylum seekers and refugees, the exterior has been maintained and efforts have been made to preserve much of the interior. The condition of the building allows us to see hints of Goldie’s work in the presence of Romanesque features in the windows and interior arches. The floor tiling is very indicative of his designs and the exposed roof timber is typical of many of the churches he built in Achonry and Elphin. The chapel has been divided with an additional floor inserted at just below the clearstory and this, while preserving the structure, detracts from the visual impact. The removal of the stained glass windows is also a major loss. The exterior combines Romanesque and Classical features in a manner that is both harmonious and well proportioned.

The Bishop of Elphin’s Residence

Built in 1878-80, the Bishop’s Residence was commissioned from Goldie by Bishop Gillooly. The building was completed in time for Bishop Gillooly’s twenty-fifth anniversary as Bishop of Elphin. The building was described as a ‘massive square stone building of three stories’ and there has not been any alteration in the view that the presbytery has over the town of Sligo and of the Cathedral from those remarked upon in the Sligo Champion. The façade of the building is offered relief from the idea of a ‘massive square’ by the addition of the extending tower to the west and the mouldings and recesses around the main doorway and windows.

The small chapel in the building is very subdued and consists, primarily, of wood panel work and carvings. The Stations of the Cross are also very much a simple affair and are reminiscent of those in the Loretto Convent in Letterkenny, also by Goldie.

The crozier, designed by Goldie and carved from Irish bog oak remains in use today. At his Ordination, the present Bishop of Elphin Kevin Doran described the crozier as a symbol of ‘continuity and communion’.

The crozier was carved by Arthur Hayball, notable for his other carvings after Goldie designs. The design was featured in The Builder in 1867 and it is fortunate that the descriptions in the article let us know that the crozier has remained as when it was first delivered to Bishop Gillooly.

The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, built in 1868-73, is very much underappreciated for the architectural gem which it is. Maurice Craig said that it was ‘a work of little-recognised originality.(Craig, 1982, p.315) Irish Cathedrals, Churches and Abbeys is so broad in coverage that it allows only brief entries for each building and this is true also of the description of Goldie’s cathedral in Sligo.(Curl and O’Neill, 2002, p.143) Jeremy Williams suggested that it had been ‘relegated to obscurity’ due to the advent of the Celtic Revival.(Williams, 1994, p.337) For all this, it is agreed by both Williams and Craig that the church is both innovative and exceptional.

The foundation stone for the Cathedral was laid in 1868, opened in 1875, completed in 1882 and dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1897. One of the unusual features of the building, remarked upon by Craig, Curl and Williams, is in the style of the Cathedral. It is the only example of a cathedral in Ireland from the nineteenth-century built in the Norma-Romanesque style.(Beirne, 2007, p.126) The building follows the outline of a typical Catholic basilica with large tower mounted by a pyramidal spire, the height of the tower reaches 210 feet. The main entrance to the building is at the foot of the tower and this portal is surmounted by a tympanum featuring the Blessed Virgin Mary and other carved figures. The arch surrounding the tympanum is treble-recessed with moulded archivolts, chevrons and rounded ornamentation. Above the doorway there is a Crucifixion beneath a marble canopy. The entire structure presents as an almost overpowering experience as on approaches the main entrance. Other entrance are decorated with the typical and symbolic fish-scale carvings in the archways, often found in earlier true-Romanesque churches.

Inside there are three aisles with three-stage naves, consisting of clearstory and gallery. The gallery layout was were a particular highlight for Craig as they stretched across the transepts, very unusual for the period.(Craig, 1982, p.315) The overall experience in the interior is one of awe. The Dublin Daily Nation reported that ‘The dim religious light so conducive to solemn thoughts, admitted through the narrow windows, pervades the interior of the Cathedral.’ The same newspaper made favourable comparisons with the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés and there are many visual similarities between the two, both in structure and in details.

The altar and the baldachin are wonderful and, when the light shines through the stained-glass windows, radiate a warming light throughout the interior. The altar and baldachin are made in hammered brass and the biblical scenes in the predella are of The Last Supper. On either side of the Tabernacle arc carvings of The Sacrifice of Isaac and The Meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek, these are made of alabaster and their translucence adds to the glow that emits from the entire sanctuary area. Directly behind the reredos is a large statue of the Virgin Mary, also in alabaster, looking down on the altar space.

The entire internal space brings together form, material and light to enhance the spiritual encounter in an experience of presence and solemnity.

Anon 2019. St Vincent’s Church, Sheffield – Wikipedia. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Vincent%27s_Church,_Sheffield> [Accessed 2 Sep. 2019].

Beirne, F., 2007. Diocese of Elphin: An Illustrated History. Elphin Ireland: Booklink.

Bowen, D., 2006. Paul Cardinal Cullen and the Shaping of Modern Irish Catholicism. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press.

Canning, B.J., 1987. Bishops of Ireland 1870-1987. Ballyshannon [Ireland]: Donegal Democrat Co.

Craig, M.J., 1982. The Architecture of Ireland: From the Earliest Times to 1880. London : Dublin: Batsford ; Eason.

Curl, J.S. and O’Neill, B. eds., 2002. Irish Cathedrals, Churches and Abbeys. London: Caxton Editions.

swords, L., 2007. Achonry and its Churches. CU Signe.

Williams, J., 1994. A companion guide to architecture in Ireland, 1837-1921. Blackrock, Co. Dublin ; Portland, OR: Irish Academic Press.