Bandon: A Case Study

In most towns and cities in Ireland there is a dominant architectural feature in the landscape and that is often a church. In the larger cities like the capital, Dublin, the increased inner city development has visually altered the landscape so that churches are not as significant a feature as they might once have been. Nonetheless, even the Church of Ireland Christ Church Cathedral still greets the visitor to the city as they travel along the quays and along the way they will see Roman Catholic Churches, such as St. Paul’s, that retain a façade facing the river Liffey.

Outside of Dublin there has been less of an impact on the topography by large scale development in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Cork city is one large urban location that still displays a Church seeking to overlook the city and assert its presence in the navigable world of the citizens. This is best demonstrated with a visual reference. Figure 1 shows a view of Cork looking toward the north-east of the city.

The large red-brick building in the central third of the image is St. Vincent’s Roman Catholic church and Presbytery; St. Vincent’s was built in the between 1851, when the foundation stone was laid, and 1856, when it was officially opened, although alterations continued to be made to the church well into the twentieth-century. At the time the church was at the edge of the city and very little of what we now see in the upper third of the image existed. The church commanded the view over the south and central areas of Cork and still is a feature readily viewed from across the city and from approaches along the north channel of the river Lee. As the city expanded northward and above the level of St. Vincent’s church, a new church was planned and completed in the middle of the twentieth-century. The Church of the Ascension is uppermost in the image and dominates the skyline in much the same manner as St. Vincent’s had throughout the latter half of the nineteenth and on into the twentieth-century.

While St. Vincent’s was built during a period of immense change in the status of the Catholic Church in Ireland and the Church of the Ascension was constructed in the midst of major social and economic change after the achievement of independence for Ireland, they both stand as assertions of the Roman Catholic church seeking to dominate the social fabric of the country and it chooses to use these buildings as a concrete expression of this position.

In this brief essay I wish to take the town of Bandon as an example of how this drive for topographical control can be imposed upon, read and visualised in the landscape. Bandon is chosen as it had a history of conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism and this conflict took place through exclusions and inclusions in the landscape of the town and its environs. During the nineteenth-century the supremacy of the Protestant faith in Bandon was replaced by that of Catholicism and as this change in the demography of the town was taking place so too was the topography as a means to inscribe this change in the landscape. The history of the religious conflict will be outlined to give a context for the architectural

alterations that occur in three examples of ecclesiastical buildings. The locations of the buildings will be discussed in terms of Henri Lefebvre’s concepts of the social production of space and his statements that ‘(Social) space is a (social) product’, that space is a ‘means of control, and hence of domination, of power’ and that ‘space embodies social relationships’ and the work of other philosophical and architectural debates around the role of architecture as a symbol of power.[1]

Bandon: An Outline History

By the beginning of the seventeenth-century native Irish Catholics that had lived in the Bandon area were excluded from the town and its hinterland after they had lost their lands to the English Crown Forces following the Desmond Rebellions of 1579-93. The redistribution of land taken from the rebels led to the plantation of English, Protestant settlers that would alter the landscape from one dominated by the native Irish to one re-ordered by the new inhabitants.

An indication of the engineering of the demographic make-up of Bandon can be gleaned from the following statement reputed to have been attached to the walls of the town:

“A Turk, a Jew, or an Atheist,

May live in this town, but no Papist.”[2]

George Bennett’s History of Bandon is a source that can provide us with a view of the status of ‘papist’ from the early years of Bandon’s establishment as a town.[3]

The Earl of Cork, Richard Boyle (1566-1643) claimed to have built Bandon as a town but in fact he had purchased the lands following the death Henry Beecher, son of Phane Beecher, who in turn had been granted the land by the Crown. [4] Attached to the grant of land to Beecher, and others, was the condition that the lands be settled with ‘English Protestant families’.[5]

After the town Charter awarded to Bandon in 1613 the progress towards an exclusively Protestant town continued.[6] One of the first acts of the burgesses of Bandon Corporation said that ‘no Roman Catholic be permitted to reside within the town’.[7] Boyle begun and completed the walling of the town of Bandon and by 1642 was able to state that ‘there is neither an Irishman nor a Papist within the walls’.[8]

The seventeenth-century in Ireland was a time of persistent violent outbreaks that pitted Catholic against Protestant and Royalist against Parliamentarian.[9]

This national turbulence was reflected in Bandon. Bennett painted a picture of savage behaviour by Catholic rebels near Bandon during the 1641 rebellion that led to the Confederate War; a ‘Scotch minister’ was forced to eat his own ‘broiled’ flesh by some members of the uprising.[10]

As a result of the hangings, murders and other atrocities committed by the Irish against the settlers, Bennett stated that no less than ‘eleven hundred women and children’ sought refuge within the walls of Bandon town and that ‘no less than one thousand funerals took place in the first twelve months of the rebellion’.[11] By the end of the Confederate War and the arrival of Oliver Cromwell in Ireland the distance between the Protestants of Bandon and the native Irish Catholics had changed utterly. Land ownership had shifted from one of largely Catholic to almost exclusively Protestant and the domination of Protestantism in Ireland and its continuation in Bandon.[12] The status of Cromwell as a figure of hate for the Irish, that maintains to this day, and Bandon’s warmth towards him during his conquest of Ireland stands to place in context the challenges that the Catholic Church would encounter in re-establishing itself in the town.[13]

Before the closure of the seventeenth-century Bandon Protestants would again find themselves, as did the rest of the country, taking a position that conflicted with that of Catholics. The Williamite War in Ireland presented Bandon with the choice of supporting their King, James II a Catholic, or William of Orange, William III a Protestant; the town opted for William.[14]

William would eventually prove to be the victor after the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, an event seen as the turning point against James. Relatively speaking, the earlier part of the eighteenth-century was peaceful in Ireland; there were active groups of agitators such as the Whiteboys but wholesale violence did not emerge until after the rising of 1798 led by Theobald Wolfe Tone. There were a number of Acts passed during the century that eased the plight of Catholics – the Roman Catholic Relief Act of 1791 being the most far-reaching in its improvements. The founding of the Orange Order, in part as a response to the improvements for Catholics, in 1795 was embraced by the Protestants of Bandon and by 1834 it had seven Orange Order lodges in the town.[15] In 1800 effigies of King James and Queen Mary were ‘hanged, shot at and consigned to flames’ while one of King William was placed on the church spire.[16]

However, Bennett also refers to the donation of land by the Earl of Bandon and support from other Protestants for the building of a Catholic church at Gallow’s Hill in 1796, just one year after the founding of the Orange Order.[17]

The Churches

The Roman Catholic church at Gallow’s Hill stood in the shadow of the nearby Church of Ireland church of 1614 that would be rebuilt in 1847/9 as St. Peter’s.[18] The Catholic church was described in bleak terms by a correspondent to the Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier in 1855.[19] The writer pointed to the elegance of St. Peter’s and said that it was ‘the most attractive building in the place [Bandon]’ but the ‘Roman Catholic chapel was a rather mean-looking edifice, situate in a back street and not erected like the fine buildings of a similar kind that I have seen in the south, in the most prominent places, so that they generally attract the attention of all who pass by.’[20]

At a meeting held in June of 1855, in the church, to discuss the erection of a new Catholic church, St. Patrick’s, it was described as ‘inferior in every respect- it was not only inferior to the chapels of towns that were far inferior to Bandon in wealth and respectability, but it was inferior as a building, it was inferior as a house of worship, to almost every house of worship that was to be met with almost in every country parish, not only of this diocese but every diocese of Munster.’[21] The same meeting heard of the perseverance of Catholics around Bandon who had maintained ‘their fidelity under many a severe trial’ but ‘now that they were rising, as it were from the earth, and looking round them, it was time that they should no longer be satisfied with such a building, it was time that they should make themselves not only equal but be expected superior to any other parish in the building they were about to erect.’[22]

This was a clear statement of the circumstance of the Catholic Church’s demoted status as reflected in the older building and the aspiration to change and reassert itself in a new, more ‘prominent’ and ‘superior’ edifice. The report of the meeting points to the status of the Church and the appearance of the church as being co-mingled and adhering to Lefebvre’s insistence that ‘social space’, here Bandon and the places of worship, could indeed embody and act as a visual expression of the power relationships between the two faiths.

In comparison to the church at Gallow’s Hill even the original Church of Ireland building, that had been financed by Richard Boyle, the Earl of Bandon, was described as ‘large and commodious, though a heavy and inelegant structure’, certainly the more dominant of the two houses of worship.[23]

The foundation stone for the new St. Peter’s was laid in 1847 and the consecration ceremony took place in 1849. According to one report there was an extremely large attendance for the ceremony and that an additional train had to be provided for visitors travelling from Cork city for the occasion.[24] Located as it was on an elevated site in the town the church and its accompanying tower would have been a commanding structure in Bandon’s landscape.

The church, Figure 2, was designed by Joseph Welland in the Gothic Revival style and its bell tower, standing at 110 feet, adds to the impressive visual impact of the building. Welland was architect to the Board of First Fruits and its successor the Ecclesiastical Commission.[25]

The large attendance at the opening of the church points to its importance for the members of its congregation and its location in the landscape reinforces the strength of the faith in the town, in accordance with the history of Bandon outlined earlier.

But, this dominance would soon be challenged by the building of two new Catholic churches.

The convent chapel attached to the Presentation Convent on the hillside, outside of the town but overlooking it is not a large building. It was constructed to designs by George Goldie and the foundation stone was laid in September 1856 and opened for mass and a profession ceremony in March 1858.[26] The church was attached to a Presentation Convent that had been founded in 1829, the same year as the Catholic Emancipation Bill was passed in Parliament.

Like St. Peter’s, the convent chapel is in the Gothic Revival style, although much smaller. There is no direct reference to Goldie as the architect of the chapel but he is mentioned as having designed it in a report in The Cork Examiner.[27] Both the chapel and the convent stand out on the north-western horizon of the town and would perhaps have even had a more imposing presence when first built, as the spread of the town up towards the convent’s location had not expanded to the extent it has done today. What is most important to note is that on leaving St. Peter’s one is at once greeted with the sight of the Catholic chapel looking down on the church and the town, Figure 3.

Although the walls of Bandon town that had sought to exclude and control the Catholic population of the hinterland by exclusion had been demolished in 1689, St. Peter’s and its predecessor had been within the area that had been bounded by them. The Convent chapel, and the later St. Patrick’s, was outside of the town boundary. This physical exclusion is overcome by a visual intrusion into the panorama that greeted the church goers attending St. Peter’s.

As one circumnavigates the exterior of St. Peter’s one meets the imposing edifice of St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic church to its south eastern aspect. As we have seen earlier, the building of St. Patrick’s was intended to reinforce the rising status of the Catholic population of the town after Emancipation. The foundation stone for St. Patrick’s was put in place in March 1856, a few months earlier than the Convent Chapel, and was attended by a large crowd of Church dignitaries, members of the public anxious to show their support for the endeavour and the architect, George Goldie. The Cork Examiner recorded an attendance of over five thousand people for the blessing of the foundation stone and the site on which the church would be built.[28]

When the church was consecrated in 1861 the attendance exceeded over four thousand within the church as well as many others who could not gain access due to the limitations of size. Again, The Cork Examiner referred to the large crowds and that half of those attempting to travel from Cork for the occasion could not be accommodated by the train services and had to be left stranded at the thronged Cork station.[29]

The significance of the building and its location in Bandon was not lost upon the newspaper’s reporter who wrote that the church would ‘in another time, mark the epoch at which Catholicism began to lift its head, and show how elastic it sprang from beneath the load of centuries; and it will speak trumpet tongued to the future ages of the zeal of the priest and people of Bandon for the glory of religion.’[30]

The church stands on an elevated site of 32 metres and looks down on St. Peter’s just a short distance away and at a much lower elevation. The tower to the rear of the church was part of the original design but was not constructed until 1920. Figure 4 shows a view of St. Patrick’s from the northern side of St. Peter’s and shows the comparative height and elevation of both buildings, while figure 5 situates both churches viewed together. The aspiration of the Catholics of Bandon to have a ‘more superior’ and ‘more prominent’ place of worship is easily read as having been achieved on the landscape of the town and its horizons when viewed from St. Peter’s.

This becomes a more profound re-calibration of social position for the Catholics viewing St. Peter’s from their newly established place of worship and is evident in figure 6 that shows a view of the Church of Ireland building from the doorway of St. Patrick’s.

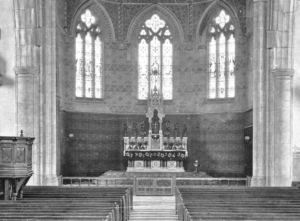

The structure of St. Patrick’s has not altered much from the designs of Goldie or from how it appeared on the day of its consecration in 1861 with the exception of the completion of the tower in 1920. The interior has been changed over the years and most especially the removal of Goldie’s original altar in 1929 when it was re-installed in a new church in the nearby village of Gaggin.[31]

The year 1929 marked the centenary of the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act and the consecration mass at Gaggin coincided with the Emancipation Centenary Mass at Westminster Cathedral, an observation made in Gaggin at the time by the celebrant, and Bishop of Cork,

the Very Rev. Dr. Cohalan.[32]

The replacement altar in St. Patrick’s is a more elaborate design than Goldie’s if we compare the present day altar with an old image of Goldie’s, figures 7 and 8. Sadly, only the altar table remains in Gaggin church, figure 9.

The descriptions of St. Patrick’s carried in the press at the time will be more eloquent than those of the present writer and this is especially true when one considers the complex context that surrounded the building of the church and the changed role of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland in the early part of the twenty-first century.

Bibliography:

Bennett, George. The History of Bandon, Cork: Henry and Coghlan, 1862.

Childs, John. The Williamite Wars in Ireland: 1688-91. New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

Dickson, David. Old World Colony: Cork and South Munster 1630-1830. Cork: Cork University Press, 2005.

Doyle, Kieran. Behind the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Protestant Power and

Culture in Bandon. Cork: K.D. Productions, 2016.

Edwards, David, Pádraig Lenihan & Clodagh Tait, eds. Age of Atrocity : Violence and Political Conflict in Early Modern Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts, 2007.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Translated by Daniel Nicholson-Smith. Mass.: Blackwell, 2011.

Lenihan, Pádraig. Confederate

Catholics at War: 1641-1649. Cork: Cork University Press, 2001.

Potter, Matthew. 'The Greatest Gerrymander in Irish History?’

History Ireland, no. 2 (2013).

St. Leger, Dr. Alicia. ‘Cork, Cloyne and Ross.’ The Church of Ireland: An Illustrated History. Edited by Dr. Claude Costecalde and Professor Brian Walker. Dublin: Booklink, 2013.

Online Resources:

Trinity College Dublin. The Down Survey of Ireland: Historical Context. Dublin: Irish Research Council, 2013. http://downsurvey.tcd.ie/history.html

Irish Architectural Archive. ‘Joseph Welland.’ Dictionary of Irish Architects. https://www.dia.ie/architects/view/4436/welland-joseph

Archival Resources:

Walsh, Fr. Christy, Annals of Presentation Convent Bandon, MS, Ref: IECCA/U17, Cork City and County Archives.

Newspapers:

Cork Examiner,

June 10, 1861.

Cork Examiner, Monday 11 June 1855.

Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent,

Tuesday 04 September 1849.

Freeman’s Journal, Saturday 22 March

1856.

Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier, Thursday 30 August 1855.

Southern Star, Saturday 21 September 1929.

Tralee Chronicle and Killarney Echo, Tuesday 11 June 1861.

- [1] Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, Trans., Nicholson-Smith, Daniel, (Mass.: Blackwell, 2011), 26-7.

[2] George Bennett, The History of Bandon, (Cork: Henry and Coghlan, 1862), 303.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

26,5.

[5] Ibid.

5.

[6] Matthew Potter, 'The Greatest Gerrymander in Irish History?’,

History Ireland, 2013, 21:2.

[7] Bennett, The History of Bandon, 29.

[8]

Ibid. 67.

[9]

For a detailed discussion on this period, the conflicts and their outcomes see:

Childs, John, The Williamite Wars in

Ireland: 1688-91, (New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007). Edwards, David, Pádraig

Lenihan & Clodagh Tait, Editors, Age of Atrocity : Violence and Political

Conflict in Early Modern Ireland, (Dublin: Four Courts, 2007). Lenihan, P., Confederate Catholics at War: 1641-1649, (Cork: Cork University

Press, 2001).

[10] Bennett, The History of Bandon, 61.

[11] Ibid.

63-5.

[12] Trinity College Dublin, The Down Survey of Ireland: Historical Context, (Dublin: Irish Research Council, 2013). http://downsurvey.tcd.ie/history.html

(Accessed: 07/01/2019)

[13] Bennett, The History of

Bandon, 150-54.

[14] David Dickson, Old World Colony: Cork and South Munster 1630-1830, (Cork: Cork University Press, 2005),

56.

[15] Kieran Doyle, Behind the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Protestant Power and Culture in Bandon, (Cork: K.D. Productions, 2016), 38-9.

[16]

Bennett, 362.

[17] Ibid.

354.

[18] Dr. Alicia St. Leger, ‘Cork, Cloyne and Ross’, The Church of Ireland: An Illustrated History, Dr. Claude Costecalde and Professor Brian

Walker, Eds., (Dublin: Booklink, 2013), 364.

[19] 'Notes From Bandon', Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier,

Thursday 30 August 1855.

[20] Ibid.

[21] 'Erection Of A Catholic Church

In Bandon', Cork Examiner, Monday 11

June 1855.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Bennett,

30-1.

[24] 'Consecration of The New Parish

Church', Dublin Evening Packet and

Correspondent, Tuesday 04 September 1849.

[25] Irish Architectural Archive, ‘Joseph Welland’, Dictionary of Irish Architects, https://www.dia.ie/architects/view/4436/welland-joseph

(Accessed: 07/01/2019).

[26] Fr.

C. Walsh, Annals of Presentation Convent Bandon, MS, Ref: IECCA/U17, Cork City and County Archives.

[27] Cork Examiner, June 10, 1861, 3.

[28] 'Church Of Our Lady and St.

Patrick, Bandon, Laying The Foundation Stone', Freeman’s Journal, Saturday 22 March 1856.

[29] Tralee Chronicle and Killarney Echo, Tuesday 11 June 1861.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Southern Star, Saturday 21 September 1929, 6.

[32]

Ibid.