George Goldie was very active in Waterford but much of his work there consisted of buildings for religious orders and he only completed one public church, St. Saviour’s, for the Dominican Order. Before moving on to his work on St. Saviour’s we will deal with his work on educational institutes and convent chapels.

St. John’s College, located at Manor Hill on the outskirts of Waterford city, is now a housing development converted to its current use by the Respond Housing Agency. The college has a long history dating back to the late eighteenth-century as one of a group of three Catholic educational centres in Waterford but in 1807 all were amalgamated into one centre – St. John’s. (Parochial History of Waterford and Lismore during the 18th and 19th centuries, 1912a, p.248) Harvey’s Parochial History of Waterford and Lismore provides a comprehensive history of the college, its origins and developments as well as important information on many of the religious institutions of the area during the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries. By the time George Goldie was called upon to design the present building, the college had been operating on the same site as a seminary for almost sixty years. (Parochial history of Waterford and Lismore during the 18th and 19th centuries, 1912a, p.253)

In 1868 Goldie was appointed to design and oversee the construction of the new college of St. John’s. The foundation stone was laid on October 27th of that year and the building was opened to students within three years, at a cost of £23,000. The seminary is a very impressive building and sits on an elevated site overlooking the surrounding landscape. The 1871 Ordinance Survey Map of Waterford shows the large edifice with the attached chapel as it looks down to the city and the nearby Ursuline and Good Shepherd Convents. The Tipperary Free Press remarked that the front of the building was ‘visible at a distance of several miles.’(Tuesday, July 5, 1870, p. 4)

As can been seen from the photographs here (Fig. 1), while certainly not ‘one of the most commodious collegiate buildings in the United Kingdom’(Waterford Mail – Saturday 25 June 1870, p.3), it was a large building and the façade conceals the full extent of the adjoining wings and rear of the complex that contained Goldie’s ‘chapel of very beautiful design.’(Fig. 2)(The Irish Builder, November 1, 1868, p. 265). The Tipperary Free Press, which was profuse in its praise for the college, declared that ‘Whether viewed in its entirety or considered in each separate detail, the work reflects infinite credit upon the talent and professional taste of the architect Mr. Goldie, whose plans have been faithfully carried out by the contractor, Mr. Barry McMullen, of Cork. (Tuesday, July 5, 1870, p. 4)

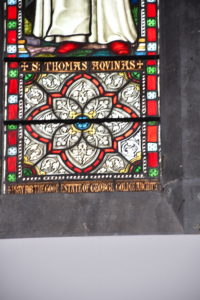

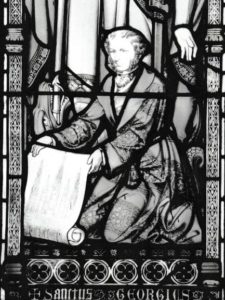

The chapel exterior (Fig. 2) is very much in the style of Goldie and reminds us of his earlier work for the Presentation convent in Bandon although in Waterford we have a more elaborate expression of his Gothic Revivalism. The chapel is also incorporated into the building as it stands in the centre of the eastern end of the interior quadrangle. Although the interior has been almost stripped bare of all religious furnishings we can see that some of the original reredos have been incorporated into the now secularised space and a section of the altar table (Fig. 3 and 4) has been retained in a separate part of the building. Goldie is referenced as having worked on the interior in a stained glass window that calls for the faithful to pray for his soul ( Fig. 5). We have seen the inclusion of windows dedicated to Goldie in churches in Cork and in Bandon but such calls for prayers for his soul can also be found in the U.K (an example in Salford Cathedral shows Goldie presenting his designs for the high altar to St. George (Fig. 6)). This might be an indication of how important the ritual of prayer and the health of his eternal soul was to Goldie given his devout Catholicism.

Not far from St. John’s stands the Ursuline Convent, now housing a refugee centre. The convent contains the Church of the Sacred Heart (Figs. 7 and 8) which was designed by Goldie along with St. Joseph’s House, also within the convent grounds.

The Ursuline convent had been founded in 1816 and had seen many expansions on the site prior to Goldie’s involvement. By 1867, fifty years after its founding, it was decided to build a new wing to accommodate the growing number of children attending school there and to allow for additional space for the community of Sisters. This would be named St. Joseph’s and is still in use today as an Ursuline School. Goldie and his then business partner Charles Edwin Child were asked to supply plans for a building that would contain ‘all that was necessary for the suitable, extensive and comfortable accommodation of the pupils.’ (History of the Ursuline Waterford: From the Annals 1816-2016, ed. Sr. June Fennelly) The building was opened in October 1869. Unlike St. John’s college, which owed much to Goldie’s Gothic influence, St. Joseph’s presents a façade that is very much devised from Classical roots (Fig. 9).

A.W.N Pugin had been asked to design a church in the complex earlier in the 1840s but, although he supplied plans, due to the onset of the Irish Famine and subsequent lack of funding the building of the church did not go ahead. (History of the Ursuline Waterford: From the Annals 1816-2016, ed. Sr. June Fennelly) It would be much later that a purpose-built chapel would be added to the convent from designs by Goldie. The Freeman’s Journal carried a Tender Notice for Builders to carry out the building of ‘a New Chapel at the Ursuline convent’ from the drawings of Goldie and Child. (June 11, 1872, p. 1). When the chapel was finally opened for the Sisters on Good Friday 1874, the convent annals record that there was great admiration for the beauty of the work, work that would continue until 1879 as Goldie finished the interior furnishing and decoration. (History of the Ursuline Waterford: From the Annals 1816-2016, ed. Sr. June Fennelly) The exterior of the church owes much to early-French Romanesque architectural design with hints of Classicism as evidenced by the Diocletian windows at the gable end to the left of the apse and the interior echoes this stance with rounded arches throughout.

The chapel has fallen out of use and, like the old convent building, forms part of a refugee centre. The altar and reredos were removed from the chapel in 1995 and installed in the Church of St. Brigid in Ballycallan, Co.Kilkenny (Fig. 10) The statues of St. Angela and St. Ursula that stood in the niches of the reredos were retained by the Ursuline community in Waterford and remain in the schools on the site.

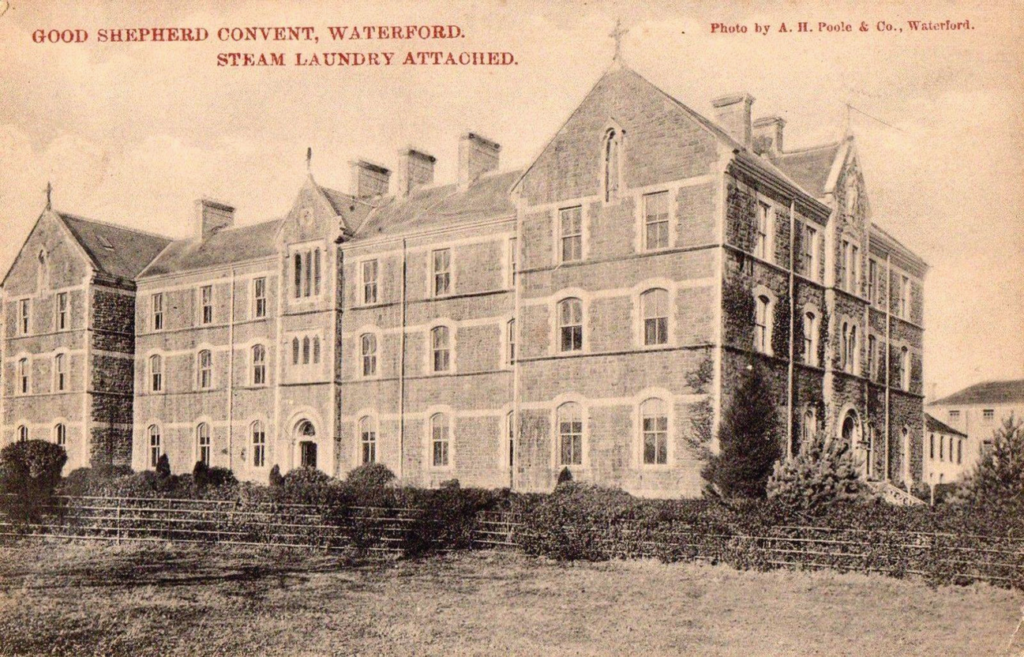

The Good Shepherd Convent – Questions of Attribution.

Fig. 11. Good Shepherd Convent

Fig. 12. Old Photgraph of Convent

Fig,. 13 Good Shepherd Convent Chapel Exterior

Fig. 14 Good Shepherd Convent Chapel Reredos

The Convent (Fig. 11)is now part of the Waterford Institute of Technology but begun its life as a Magdalen Asylum. The building that now stands is a rebuilding of an earlier convent on Hennessy’s Road that had stood from the early years of the nineteenth-century and housed the Presentation Sisters. (Finnegan, 2004, p.89) It is difficult to identify what buildings were designed by Goldie in the Good Shepherd Convent Grounds. Harvey and co. suggest that Goldie’s input was limited to the industrial school and his name is not mentioned by Finnegan. (Parochial History of Waterford and Lismore during the 18th and 19th centuries, 1912a, p.259) Old images (Fig. 12) describe the building shown here as the convent and industrial school so it is most likely that this is the building designed by Goldie and it is in keeping with his design for the St. John’s college. It is probable, given the work that Goldie had been involved with in Waterford, that he might be contracted to bring forward the designs for the building that we see here, it is also the case that this building is identified by former Magdalens from the twentieth-century as the industrial school and there seems to be no other building that could match the demands of convent, industrial school and attached chapel on the site. https://www.waterfordmemories.com/virtual-tour

The chapel (Fig. 13) itself seems to be of a later design and is unlike the other convent chapels Goldie designed for the nearby Ursuline convent and St. John’s college. One would also expect that, given the proximity, the chapel stained glass would contain a reference to Goldie but this is not the case. However, it is similar to other large churches that Goldie had built in other counties. The interior, which retains the reredos (Fig. 14) and other internal fittings, does contain elements familiar to us from other churches such as the Goldie Chapel in Nano Nagle Place, Cork and the original reredos in the nearby Ursuline convent. This is all visual evidence that indicates this could be a chapel built to Goldie’s designs but there is, as yet, no other support to establish this as being a work by Goldie. The Buildings of Ireland inventory does not attribute the chapel or the adjacent convent to any architect.

The three buildings stretching from St. John’s College as far as the Good Shepherd Convent form an impressive series of landmarks on the landscape of the city and point to the strength of Catholicism in the area, a strength that we learn of from Finnegan and from Harvey’s Parochial History of Waterford existed even prior to the advent of Emancipation.

Fig. 15 St. Saviours’ Exterior

Fig. 16 Rosary Altar, St. Saviour’s

Fig. 17 Pulpit, St. Saviour’s.

Fig. 18 Interior St. Saviour’s

Fig. 19 Present Main Altar, St. Saviour’s.

Goldie’s most important and substantial intervention in the architectural landscape of the city, in terms of a public ecclesiastical building, is St. Saviour’s church (Fig. 15). Sadly, much of the interior furnishings have been altered or removed. The site for St. Saviour’s came into the possession of the Dominican Order in Waterford on ‘the first Tuesday of October’ 1873 and Goldie, Child and Goldie,(George’s son Edward), were at once engaged to produce designs for ‘a Romanesque church.’ (Parochial History of Waterford and Lismore during the 18th and 19th centuries, 1912b, p.219) An advertisement seeking tenders for the work on the church was placed in The Freeman’s Journal in February 1874 and the foundation stone was laid in May 1874. When the church was opened in December 1877 it was described in glowing terms in The Tablet and the Italianate style was described as ‘exquisitely elaborated.’ The Rosary side chapel (Fig. 16) is still extant as is the pulpit (Fig. 17) designed by Goldie but not put in place until 1890 (Weekly Freeman’s Journal) and they lend us some idea of how the church would have appeared to mass goers of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries prior to the destructive alterations that would later take place in the Sanctuary area. A comparison between figure 18, which shows the interior of the chapel as it was prior to the installation of Goldie’s pulpit and figure 19, which shows the Sanctuary area as it is today, demonstrates both the structural and liturgical changes that have impacted on the completeness and integrity of Goldie’s design. According to information from the Dominican Order in Waterford, the original altar was taken apart in 1967, most likely to conform to the interpretations of Vatican II, and parts were relocated to a monument near the city quays. The exterior remains unaltered and stands out as a superb example of the Italianate style that it was considered to be in the nineteenth-century and it presents as a landmark contribution to the present cityscape of Waterford as one moves into the heart of the city from the river and the quays.

Goldie also made a submission of plans for the design of a new altar for the Church of St. Joseph in Dungarvan, not far from Waterford city, but the plans by Pugin and Ashlin were accepted. Goldie did, however, design a stained glass window for the Augustinian church in the same town in 1869. The window was dedicated to the memory of Dr. John Coman, a local surgeon that was held in high regard due to his work on an earlier cholera epidemic in the area, and an altar was also erected at the same time but it is not clear from the newspaper reports of the day if this can be attributed to Goldie.

The Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity saw an intervention by Goldie in 1883-6. The Cathedral was built during the eighteenth-century and was redecorated toward the end of the nineteenth-century when Goldie designed a ‘magnificent baroque pulpit’ along with chapter stalls and Bishop’s chair, these were all made in oak by Buisine and Sons of Lille. (Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity Waterford, n.d.) This may be an understatement on the amount of work carried out on the church as a meeting held in Waterford and reported in the Waterford News and Star suggests that there was an almost total rebuild of the interior, including the Sanctuary, baldacchino, main altar, side altars, Stations of the Cross and other works.

Goldie is also identified as the designer of an altar for St. John’s parish church that ‘as a work of art is believed to be equal to the best altars in the country.’ (Waterford News and Star , Friday, November 01, 1929, p.2).

An interesting aside to Goldie’s connection with Waterford can be noted from his brother, most likely Francis, the Rev. Goldie, having presented a lecture at the Catholic Young Men’s Society in the town in 1863.

Bibliography:

Anon 1912a. Parochial history of Waterford and Lismore during the 18th and 19th centuries. [online] N. Harvey. Available at: <http://archive.org/details/parochialhistory00nhar> [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Anon 1912b. Parochial history of Waterford and Lismore during the 18th and 19th centuries. [online] N. Harvey. Available at: <http://archive.org/details/parochialhistory00nhar> [Accessed 1 May 2019].

Anon n.d. Cathedral of the Most Holy Trinity Waterford. Available at: <http://snap.waterfordcoco.ie/collections/ejournals/128129/128129.pdf> [Accessed 29 May 2019].

Finnegan, F., 2004. Do Penance Or Perish: Magdalen Asylums in Ireland. Oxford University Press.