Roscommon Churches:

In the immediate aftermath of the Famine, Goldie was involved in designing, or contributing to the design of, a large body of work in the counties of Roscommon, Sligo and Mayo. The diocesan structures crossed the different county bounds so that parts of Roscommon are in the Diocese of Elphin and others are in Achonry. Within Roscommon Goldie designed St. Patrick’s, Castlerea, The Immaculate Conception, Strokestown, St. Baoithín’s, Tibohine, St. Joseph’s, Boyle, and the Cathedral of St. Nathy’s, Ballaghaderreen. He is also reputed to have made additions to the former Courthouse in Roscommon town and he designed a memorial to the late Bishop of Achonry, Rev. Dr. Browne, for the same church. A further memorial to Rev. Dr. Browne was a complete sanctuary layout including altar, reredos, tabernacle and reputed to be in the ‘Parish Chapel’ but as no town or church name is given it is difficult to say for certain where it was located, we will return to this later.

Cathedral of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Nathy

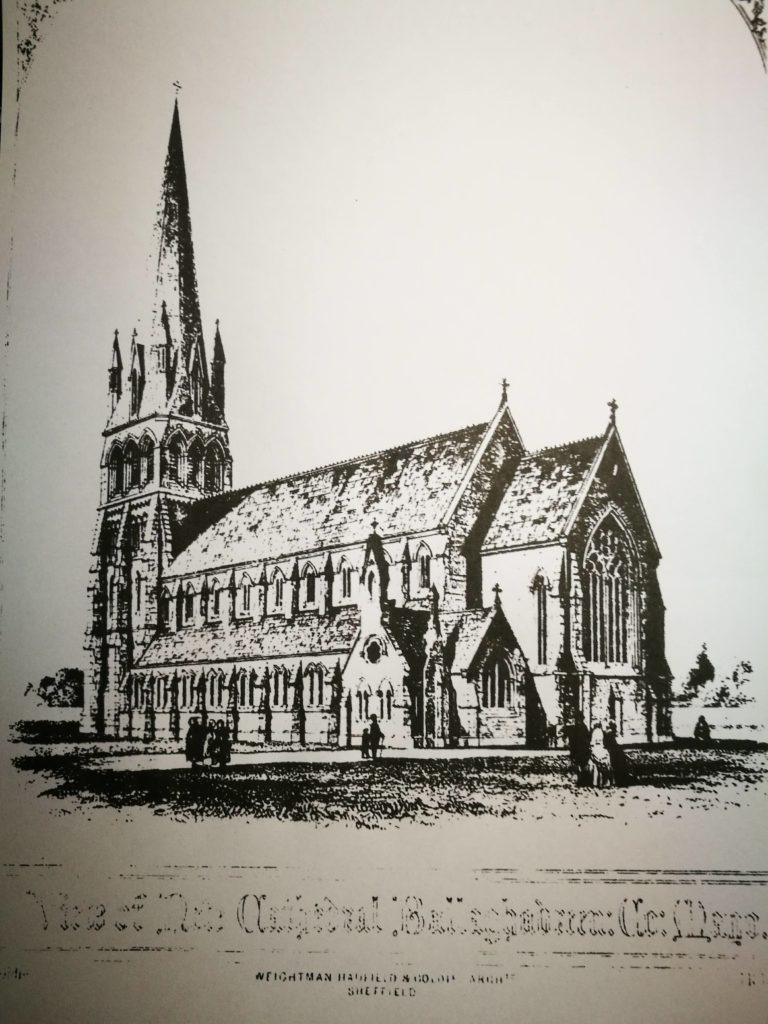

When the Cathedral of St. Nathy’s was opened and dedicated to the Blessed Virgin and St. Nathy on November 11th 1860 it was far from complete. The Freeman’s Journal, and others, carried reports of the work in progress and the circumstance of the building along with descriptions of the design and interior furnishings. The foundation stone had been laid on August 9th 1854, the feast day of St. Nathy, patron Saint of the Diocese of Achonry. The architect present at the time was not George Goldie but John Sterling Butler who had also designed the Church of the Immaculate Conception in nearby Kilmovee, Co. Mayo, in the Diocese of Achonry.(swords, 2007, p.78) The Civil Engineer and Architects Journal informs us that the initial course of block work had been commenced to the designs of Butler but that work ceased and the project was then taken over by Goldie- the new architects were limited in what they could do with the site as a result.

The Cathedral was to replace a chapel which had been deemed ‘unfit for the sacred purpose for which it was applied.’ According to Liam Swords, the previous church was a ‘square barn like place…hidden away in a gloomy part of the town.’ (Swords, 2004, p.356) Clearly, as with Bandon and other towns, this new Cathedral was a symbol of a re-emerging Catholic Church even at a time of extreme poverty. One of the prime reasons for the Cathedral being uncompleted at the time was a lack of funds, such a conclusion should not come as a surprise given the perilous state of the area during and after the Famine.(Swords, 2004, pp.356–7). Newspaper reports of the dedication of the Cathedral all testified to the poverty of the parish. The Freeman’s Journal stated that the ‘large and beautiful Gothic church, which, though erected in the poorest parish in Ireland, would grace the richest and most prosperous locality in the country.’ The same newspaper pointed out to its readers that the Cathedral had been built in a remote area, out of the reach of railway lines, in a wide expanse of bogs and in ‘a comparatively sterile country.’ One of the legacies of the Famine was a massive decrease in the population of the Diocese of Achonry and in the counties of Roscommon, Mayo and Sligo, this was due to emigration and mortality. Liam Swords tells us that while some parishes had decreases of 30% others had a loss of upwards of 60%.(Swords, 2004, p.170) In some of the parishes that Goldie built there was a surprisingly low loss of lives and population, Gurteen, Ballymote, Charlestown and Ballaghaderreen had all losses in the mid-to-late 20%.(Swords, 2004, p.170). Swords points out that in most of these towns the landlord was Viscount Dillon and his agent was Charles Strickland, who ‘played an active role in providing relief during the famine.’(Swords, 2004, p.170). Dillon donated the site on which the Cathedral was built and also supplied the limestone material from quarries on his estate. There are stained glass windows in the chapel dedicated to the Stricklands. (Galloway and Simms, 1992, p.22) In Sligo Cathedral there are stained-glass windows dedicated to the memory of Jerrad and Anne Strickland, the parents of Charles. Thomas Strickland was a relation of Charles and he attended, along with his wife and Charles, the original foundation stone laying ceremony for the Cathedral. Thomas had studied at Ushaw College at the same time as Goldie and Thomas’ son spent some time with Goldie when he was studying in London.(Carpenter et al., 2015) Thomas’ son was Walter Strickland, author of the Dictionary of Irish Artists.

The Cathedral was one of the earliest works to be commenced by Goldie in Ireland. It is interesting that a number of his works in the west of Ireland had connections with the Stricklands and we might assume that this may have been influenced by his early acquaintance with the Strickland family. Relationships mattered in church architecture of the period; for many of the works commissioned in the Diocese of Elphin by Bishop Laurence Gillooly he sought out Goldie whom he had known from his work in St. Vincent’s, Sunday’s Well, Cork. We might also refer to the controversy involving Edward Welby Pugin and George Ashlin in the competitions for St. Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh and SS. Peter and Paul’s, Cork, to show how family connections and friendships could influence the selection of architects.(Wilson, 2004, pp.234–5) Peter Galloway suggests that the Cathedral was designed by Goldie’s partner, Matthew Hadfield, because he had corresponded with A.W.N. Pugin in 1849-50 but Goldie’s connections with the Stricklands might be a more realistic assumption.(Galloway and Simms, 1992, p.21)

The Cathedral was finished by W.H. Byrne who completed the tower and spire but the rest of the body of the Cathedral remains as Goldie designed it. The tower built by Byrne is very different from Goldie’s, the buttresses are reduced in number as are the wall arcades and lancet windows, the spire-lights are incorporated into the spire and, as a result, lose a sense of definition. We don’t have a view of the front of the tower as envisioned by Goldie but the additional height that seems to be present in Byrne’s tower suggests that he needed more room for the larger pointed window and clockface while the belfry added an extra tier not included in Goldie’s design. Galloway has suggested that Byrne’s tower and spire are at odds with the proportions of the body of the church and perhaps if Goldie’s design had been continued it would have been more unified.(Galloway and Simms, 1992, p.22) The open ceiling revealing the timber trusses was as a result of financial considerations as to render the ceiling would have added to the cost of the building.

Goldie’s design displays many of the elements that can be found in his other churches. The gable at the east-end, (apse), is very like his work in the Presentation convent, Bandon and the chapel exterior of St. Joseph’s in Waterford. The rock-faced masonry can be found in St. Patrick’s, Bandon and carved limestone features are typical of churches by Goldie in the area, such as Bohola and St. Baoithín’s. The reredos and altar are very much in keeping with many of his churches, both in Roscommon and throughout Ireland. The high altar was made to Goldie’s designs by Henry Lane, Dublin, and Caen stone and Irish marble were used for the altar and reredos. Goldie believed that the church should be a place that would inspire those who entered and allow them to leave the temporal world behind as they entered the sacred space. The lofty heights of the reredos and ceilings, the light from the clerestory windows and the heavenly reach of the pointed arches would certainly have brought such an effect to the congregation as they left the profane world behind them.

Goldie Drawing for Ballaghaderreen

Exterior of St. Nathy’s

View toward altar of St. Nathy’s

Reredos in St. Nathy’s

View toward entrance to St. Nathy’s

Exterior View of St. Nathy’s

The Immaculate Conception, Strokestown

There are few references to Goldie being the builder of the Church of the Immaculate Conception. The Dictionary of Irish Architects attributes the work to him as does Fr. Francis Beirne.(Beirne, 2007, p.156) One reason for assuming this to be the work of Goldie is that the Bishop of Elphin at the time of its construction was Laurence Gillooly. The church was built between 1860 and 1863. A large donation of over two-thousand pounds toward the construction cost was made in 1861 by the Very Rev. Dean McDermott. If Beirne is correct then many of the features of the church as built by Goldie remain. The large scale renovation and extension of the Church of the Immaculate Conception that was carried out in 1959-60 retained the altar, reredos and stained glass put in place by Goldie.The church roof was lowered and two new bays were added to provide additional seating. It is difficult to discern how the original building might have appeared, both internally and externally, as the lowering of the roof will have altered significantly the proportions of the building. Today, the tower and belfry appear to be severe and abrupt as the sloped roofs of the nave cease suddenly to descend to the side aisle roofs. Fortunately, we can still experience the magnificent reredos and rose window behind within the chancel.

Strokestown View towards Entrance

Strokestown View towards Altar

Strokestown Reredos

Strokestown Interior View

Strokestown Exterior View

St. Joseph’s Church, Boyle.

St. Joseph’s Church in Boyle was consecrated and opened in 1882. It was a tumultuous period in the history of the town and indeed the entire county as the Land Wars were becoming more intensive. As we have seen with Ballaghaderreen, the general state of the people of Roscommon was one of impoverishment after the effects of the Famine and the continuing struggle to survive.

Throughout the counties of Sligo, Mayo and Roscommon their was intense agitation around the issues of landlordism, rents and land ownership. Bishops, such as Patrick Moran of Ossary, and Laurence Gillooly, of Elphin, had expressed support for certain candidates in the General Election of 1880 but their advice was ignored by the electorate who chose followers of Charles Stewart Parnell, a grouping described by Bishop Moran as ‘extreme Home Rulers’ and whom Gillooly saw as ‘extreme politicians.’(Swords, 2004, p.236) Swords provides a very comprehensive analysis of the conflicts and land campaigns that took place in the Diocese of Achonry during the period and deals with many of the individuals and local protests that took place in the area.

In Boyle, in 1880, there was held one of the ‘largest and most enthusiastic demonstrations’ in favour of land reforms. The Sligo Champion’s report on this meeting gives a very real sense of the strength of feeling in the Roscommon area. Another article outlining briefly a history of Boyle contrasts the prosperity of Boyle prior to the Dissolution of the Monasteries with the poverty that became widespread among the Catholic peasantry under the yoke of the Penal Laws. The same report described Boyle of 1880 as ‘one of the poorest, most neglected, and most decayed of the towns of Ireland’ and the author viewed the new Catholic church, only under construction at the time, in stark contrast to the grandeur of the once magnificent Abbey at Boyle. The ancient Abbey of Boyle was ever-present in discussion of the new church and seen as a past taken from the Catholic majority that was now, in Boyle as throughout the country, reimposing itself on the landscape and character of the nation. In his sermon on the occasion of the church’s consecration, the Rev. J. Healy spoke of the blood of martyrs and the resurrection of the people and how they had ‘cast off their bonds and risen to their feet.’ Healy used the building of the church as a metaphor for the newly ‘awakened life and youthful energy’ of the parish. It is in this turbulent time, after the ravages of the famine, the conflicts around tenancy and security of tenure, the looking to an ancient past in ruins and the rising of a reinvigorated Catholicity , that St. Joseph’s church was built.

The church was built in ‘late thirteenth century Gothic style’, cruciform in shape and with the western tower ‘rising 60 feet.’ The tower and spire were extended in the 1950s The reredos stretched to over thirteen feet in height and contained statues of the four evangelists and there were side altars dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and to St. Joseph . Unfortunately the church was burned down in 1977 and nothing remains that would allow us to examine the internal furnishings designed by Goldie although the tabernacle was rescued .

St. Patrick’s, Castlerea.

By the date of its consecration, both George Goldie and Laurence Gillooly, Bishop of Elphin, had died. Goldie had died in St. Servan, Brittany, in 1887 and Bishop Gillooly had passed away in 1895, the year just before the church’s dedication. The foundation stone had been laid in 1893 . Although a number of contemporary papers attribute the design of the church to Bishop Gillooly it is most likely that it was designed by Goldie for Gillooly and that the push to have the church completed after the death of the architect gave rise to the Bishop being awarded credit by the press of the day. The Freeman’s Journal says that the church was designed by Bishop Gillooly in consultation with John Scannell; Scannell had been the clerk of works on a number of buildings designed by Goldie. However, The Irish Builder and Building News both attribute the design of the church to George Goldie. The National Inventory of Irish Architecture (NIAH) also credit Goldie with the design of the church. It is suggested by the NIAH that the high altar was completed by a different architect at a later date but, visually, the description of the reredos provided by The Freeman’s Journal concurs with the photographic evidence. The Journal speaks of ‘a Calvary scene’ ‘flanked by niches containing statues of St. Peter and St. Paul and an altar table supported by ‘columns of Connemara marble’ all of which can be seen in the photograph shown here.

The exterior of the church displays similarities with the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Sligo, by Goldie and has many of his signature Norman-Romanesque tendencies such as the crisp, clear lines of the tower but mixed with the Gothic pointed arches. The Church of the Immaculate Conception, Sligo has an interior that is very much echoed in St. Patrick’s. The exposed truss work is a familiar sight in his churches, whether by design or necessity. The stained glass, much of it in place at the time of the dedication in 1896 and described in The Freeman’s Journal, creates a contemplative space that would surely have offered a moment of awe for members of the congregation and transform the experience of entering the church to one at odds with the grey, limestone exterior.

Castlerea View Toward Altar

Castlerea View Toward Entrance

Castlerea Side View

Castlerea Reredos

Castlerea Front View

St. Baoithín’s, Tibohine.

St. Baoithín’s is located in the Diocese of Elphin and it was consecrated on June 9th 1861. The church is very much of the period and typical of Goldie in that it provides a strong presence on the landscape, gives shelter to a large congregation and creates a space for a spiritual encounter through the harmonisation of light and form. Built in a simple Gothic style, the presence of the original sanctuary area, including reredos, altars and altar rails allows us to experience the church as it would have been intended. Although on a very much reduced scale when viewed next to some of the other churches by Goldie in Roscommon, we can see the function of an enclosed space for worship and communion. The rough surface of the locally sourced exterior walls create an impression of durability and stability while the interior, graced by the light of the rose window in the chancel and the lancet windows throughout, soften and transform the transition from the exterior mundane world to the sacred and sanctified space.

Extension to Roscommon Parish Church and Memorial to Bishop Browne.

The Roscommon Town Heritage website provides an interesting history of The Harrison Hall in the town. The buildings begun life as a courthouse designed by George Ensor in 1762. It was located in the market square and The Dictionary of Irish Architects, referencing a number of contemporary building journals, mentions Goldie as designing a number of additions to the Hall after it had been bought by Fr. John Madden P.P. in 1829 and converted into a chapel just after Catholic Emancipation.(Beirne, 2007, p.114) According to Beirne, the chapel acted as the parish church until the construction of the Sacred Heart Church in the town in 1903.(Beirne, 2007, p.114) The Roscommon Town Heritage website, and Beirne, both inform us that the church was converted to a bank in 1972 and continues to operate as one to this day.

The fact that the building was known as the parish church of the town helps us to identify it as the site for which Goldie also designed the high altar, reredos, tabernacle and additional furnishings. A monument was also built as a memorial to the Bishop of Elphin, Rev. Dr. Browne.

The record of Goldie’s contribution to the architectural landscape of Roscommon and his impact on the ecclesiastical make up of the county is at times sparse but it is also evident that he did make a major contribution. There are other churches in the county that lack an attribution and these too may have been part of Goldie’s oeuvre . It is clear that a lot more work needs to be done on the church architecture of the county to secure a clear picture of the social and ecclesiastical history of the area in the nineteenth-century. Liam Swords’ A Dominant Church and Francis Beirne’s Diocese of Elphin: An Illustrated History have made major inroads into this important work.

Bibliography:

Beirne, F., 2007. Diocese of Elphin: An Illustrated History. Elphin Ireland: Booklink.

Carpenter, A., Figgis, N., Arnold, M., Butler, N. and Mayes, E. eds., 2015. CONNOISSEURSHIP AND THE ART MARKET. In: Art and Architecture of Ireland Volume II, Painting 1600-1900, 1st ed. [online] Royal Irish Academy.pp.11–22. Available at: <http://www.jstor.org.ucc.idm.oclc.org/stable/j.ctt14jxtwj.12>.

Galloway, P. and Simms, C., 1992. The cathedrals of Ireland. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen’s University of Belfast.

Swords, L., 2004. A dominant Church: the Diocese of Achonry, 1818-1960. Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Columba Press.

swords, L., 2007. Achonry and its Churches. CU Signe.

Wilson, A., 2004. The Building of St. Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh. Irish Architectural and Decorative Studies, VII, pp.233–65.