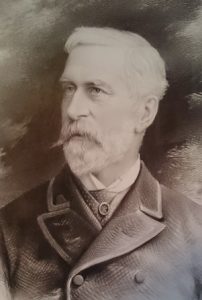

George Goldie was born in York, United Kingdom, on June 9th, 1828 and died in Saint Servan, Brittany, on March 1st, 1887. Goldie was, what was termed in the nineteenth-century, a ‘cradle Catholic’, that is, he was born into that faith rather than being a convert from Anglicanism. George’s father was the son of George Sharpe Goldie and Sophia Osborne.[1] George Sharpe Goldie predeceased Sophia and Sophia at this point went to Rouen and converted to Catholicism. George’s father, also George, was a medical doctor who was active in the Catholic Emancipation movement and would marry Mary Anne in 1828, a Catholic and daughter of Joseph Bonomi.[2] Joseph Bonomi was an Italian who also had a son, Ignatius, who would also become an architect. George had eight siblings of whom three died at a young age and of those that lived Charles became an artist, Edward would become a Monsignor and Canon of Leeds, Francis became a Jesuit priest and writer, Mary became a nun who resided at St. Mary’s Convent, York as Mother Mary Walburga and Catherine who also became a nun in the same convent and adopted the name Mary but died at the age of twenty-eight.

In 1855 George married Marie Madeleine Rose Simeon Stylite Sioc’han, the eldest daughter of the Vicomte Sioc’han de Kersabiec, from Kersabiec in Brittany, the priest that performed the ceremony was the Rev. J. Bonomi, perhaps a cousin or uncle of the groom.[3] The Tablet noted in 1919, that the de Kersabiec was an old Breton family that had fought as part of the Papal Zouaves.[4]

Given this background it seems natural that if George was to become an architect that he would also have a desire to practice his craft in the design of Roman Catholic edifices. Pope Pius IX awarded him the Cross and Order of St. Sylvester in 1877 for his work ‘as a Catholic architect.’[5] His father’s activities in support of Catholic Emancipation would almost certainly have endeared him to the Catholic Church in Ireland and aided him in his work in ecclesiastical architecture.[6]

George attended Ushaw College in Durham, a college with connections to the Pugin family of architects and included Nicholas Wiseman amongst its alumni. A.W.N. Pugin designed the chapel at Ushaw and his two sons Edward and Peter attended there and also designed the Junior House and the Refectory, respectively. Goldie met with A.W.N. Pugin at Ushaw and sought to become a student of his but ‘Pugin recommended him to enter the offices Weightman & Hadfield in order to gain more practical knowledge of architecture and building than Pugin could impart.’[7] Goldie remained with Weightman & Hadfield from 1850 until 1860.[8] Goldie would also have a rivalry with Edward Pugin when in Ireland, a dispute that was carried on through the press of the day.

Goldie along with J.J. McCarthy and Pugin & Ashlin had been asked to supply designs for a competition to design St. Colman’s Cathedral in Cobh. Goldie and McCarthy were not very happy with the competition going ahead without some assurances against possible bias on the part of the judging committee. Ann Wilson has shown that the Bishop of Cloyne, William Keane, had already corresponded with Ashlin & Pugin prior to the competition on the matter and that Ashlin’s brother was a priest in Cobh at the time.[9] George Coppinger-Ashlin, the Coppinger had come from his mother’s family, belonged to a family that had strong businesses in the area, were very well connected to the diocese; Dr. William Coppinger had been a Bishop of Cloyne and the Bishop of Cloyne at the time of the competition had been ‘mortgagee for the Ashlin-Coppinger family trust.’[10] In the end the assurances sought were not given and the contract was awarded to Pugin & Ashlin.

George became involved in another long and protracted pubic dispute in the form of a court case while a junior partner with Weightman and Hadfield. The case was between the builders Walter and William Doolin and the Rev. James Dixon and other members of the Vincentian community at Phibsboro and Castleknock and rested on a claim for unpaid costs incurred in alterations that had taken place as the building of St. Peter’s, Phibsboro progressed. According to reports of the case it was some of the alterations were being suggested while work was on going by Rev. Thomas McNamara that resulted in a dispute about the safety of the towers that had been added to the designs. The case was a long a protracted affair and was widely covered by the press of the day with special attention being afforded to it by The Irish Builder.

In the prolonged court case one lawyer stated that ‘though I am not engaged to defend Mr. Goldie, I must say that he did not do wrong; and I cannot avoid saying that the only pleasing and redeeming feature of in this disgraceful case, as far as I am concerned, is the fact of having made the acquaintance of Mr. Goldie.[11] Richard Denny Urlin, M.R.I.A. and later barrister described Goldie as a genius in the context of St. Peter’s. [12]

St. Peter’s was altered in the early twentieth-century after a hiatus in its construction as result of the court case and the incompletion of the tower to Goldie’s designs, completed by Ashlin & Coleman. These alterations and, in some cases removals, of work by Goldie from the interior of churches and the loss of complete buildings such as the Church of St. Joseph, Boyle, that was burned down in 1977 have had an impact on a full appreciation of Goldie’s work in Ireland. St. Mary’s in Convoy, Donegal, was almost entirely demolished and replaced in the early 1970s, recently the closure of St. Vincent’s, Sunday’s Well, Cork, has resulted in the removal of much of the interior décor, (fortunately with parts being relocated to St. Peter’s in Phibsboro and the Vincentian College in Castleknock, also designed by Goldie) have meant that even though his work endures it is displaced from its original context. Another recent development at the South Presentation Convent, also in Cork, has seen the small but interesting example of his work incorporated into the Nano Nagle Heritage Centre. The reredos and altar that once were set in the Ursuline Convent in Waterford are now to be found in the church of St. Brigid in Ballycallan, Kilkenny.

We cannot be sure of how Goldie would feel if he could see these changes to his work taking place but we can learn of his appreciation of architecture and his thoughts on the spiritual importance of the Church and its role in the lives of the Church’s congregation from reading some of the limited writings that have been handed down to us in journal articles and lecture transcripts.

Goldie’s brother, Francis, S.J., contributed numerous essays to and edited the Jesuit publication The Month over prolonged period towards the end on the nineteenth-century, and his brother Charles also made some contributions to the same journal. George had eleven articles published in The Month that focused mainly on the spirituality and perseverance of French Catholicism and on visits he made to convents and churches in France. His descriptions of the architecture of the ecclesiastical buildings he visited provide us with hints to his strong attachment to the idea of the church buildings as a statement of devotion to and the strength of the Catholic faith. An example of his language from an essay dealing with a visit to the convent of the Little Sisters of the Poor, in Brittany is a clear endorsement of his strong faith and belief in the resurgence of Catholicism:

There are few Catholics who have not now and then, in the course of recent years of trial and persecution of the Church not been tempted to lift up their clasped hands to heaven and ask God for some sign that His divine hand had not left the rudder of St. Peter’s bark. And yet a moment’s thought, a rapid flight of memory of the world’s surface, far and near, would be all-sufficient to console us and afford an over-whelming sentiment of joy. It would give us the most entire certainty that not only was our Blessed Lord steadfastly directing the course of His Divine Institution , the Catholic Church, amidst the rocks and breakers of our age but, that who have eyes to see and ears to hear, He was performing in our midst miracles of grace as marvellous and sublime as were ever granted to the Church in her moments of the most complete triumph and prosperity. We need hardly suggest, as some special sources of consolation, the glorious spectacle of Christ’s Vicar, Pius the Ninth, erect and steadfast in the Vatican, the united, the universal devotion to his person of the whole Catholic world; the intimate bond of parsons and people never drawn so close in the whole history of the Church; the singular faithfulness and purity of the clergy; the rapid growth of the Catholic church in America and Australia.[13]

On architecture, we have a lecture given in Sheffield in which he states when comparing Classical architecture in church building with the Gothic

Its [Italian Architecture from the sixteenth-century onwards] productions have been various, very noble in its appliances to domestic architecture and to some few Churches, chiefly abroad, though, as I have said before, it never can demand or obtain that sympathy in Ecclesiastical Architecture that the Gothic style always must, simply because the one is Pagan and the other Christian in origin.[14]

And further:

It has been only within the present century that attention has been called to a vigorous effort made for the revival of the departed glories of the middle ages and a most happy abandonment of Pagan types almost generally accepted on behalf of Christian Architecture.[15]

It can be seen from his writings extant, of which the two quotes given are merely examples of an eloquence that express his devotion to Catholicism and to its expression in its architecture, that Goldie believed in his building as a statement of his faith. We are fortunate in Ireland to have access to these statements in his remaining buildings.

[1] Gillow, Joseph, A Literary and Biographical History, or Bibliographical Dictionary, of the English Catholics from the Breach with Rome, in 1534, to the Present Time, Volume 2, (London: Burns & Oates, 1885), 510-13.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The Illustrated London News, September 15, 1855, 326.

[4] The Tablet, November 11, 1909, 22.

[5] The Waterford News and General Advertiser, July 13, 1877.

[6] Gillow, Joseph, A Literary and Biographical History, 510-13.

[7] Hadfield, Cawkwell, Davidson and Partners, 150 Years of Architectural Drawings-Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson, Sheffield. 1834-1984, (Sheffield, 1984), 14.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ann Wilson, ‘The Building of St. Colman’s Cathedral, Cobh.’, Irish Architecture and Decorative Studies VII, 2004, 233- 65.

[10] O’Dwyer, Frederick, ‘A Victorian Partnership- The Architecture of Pugin and Ashlin’, 150 Years of Architecture in Ireland, John Graby (ed.), (Dublin, 1989), 55-62.

[11] The Irish Builder, December 15, 1868, 313

[12] The Evening Freeman, May 10, 1871, 2. Urlin, Ethel Lucas Hargrave, Memorials of the Urlin Family, (Sussex: Private Publication, 1909) 35.

[13] Goldie, George, ‘La Tour St. Joseph: Mother House of the Little Sisters of the Poor.’, The Month, April, 1875, 448-55.

[14] Goldie, George, A Lecture on Ecclesiastical Architecture Delivered at a Meeting of The Young Men’s Society, Sheffield, (London: Richardson and Son, 1856).

[15] Ibid.